So, you live in Orlando. (sorry to hear it, bud)

It’s Friday, and the weekend beckons. Everyone and their mother is either booking it to various theme parks or hitting the bars. But no, not you.

You, being the beautiful, cultured and ever virile scholar of the cinematic arts, will set out for alternative kicks. The sort that reside within the confines of a cinema, and presented in celluloid, no less.

But!

You’re tired of the homely state of multiplexes: lousy parking spaces; soggy carpets; unrelenting, wild-eyed children wagging dirty fingers; a teenage work force that couldn’t give a damn about what you’re here to do. (Watch a movie?!)

If this is you, I recommend a trek into the heart of Orange county, Florida. There, nestled among the Florida live oak, you’ll find the Enzian theater. A marvelous local gem. Independent, hip, and sporting an outdoor bar and concession stand touting all your favorite movie treats.

The Enzian is revered for its thoughtful, fan curated programing. From monthly themed features (pride month, holiday favorites, cult classics, retrospectives) to kid-centric weekend screenings, the non-profit cinema exhibits entertainment for everyone.

It’s a welcomed repertory home for movie fans in “the know,” and a point of envy for those that live in the fringes of cinema culture—small towns with little investment in the art form (Me!)

Back in January, I sought out a screening of THE BRUTALIST in 35 millimeter (mm). From where I live, a drive to the Enzian called for a little over three hours of my day. Was it worth the trek? Absolutely. Not just because I witnessed a “great” movie, but because of the format in which it was presented.

Celluloid.

You don’t have to be an ardent cinephile to grasp the concept of physical celluloid. Whenever you hit snap on a film camera, light is captured in the lens, causing a chemical reaction to occur on the strip of film. This results in an “imprint” on the light-sensitive strip of celluloid.

An image has been captured on film.

In the case of motion pictures, the film is developed in a lab. Once “mastered” it is fed through a projector at a speed of twenty-four frames a second, emulating the natural speed in which humans perceive motion.

A little sound mixing here, and color correcting there, and…bingo! You’ve developed a series of moving images.

Though it wasn’t the much-touted 70 millimeter screening, I was still happy with the clarity of detail and color shown on 35mm. With film, the images projected on screen come the closest to resembling reality. This means deep color saturation, along with whiter whites and blacker blacks.

In most cineplexes, you’ll find that trailers run for an ungodly length of time. Before the feature begins, said cineplex will hammer home that you are, in fact, watching a movie in their theatrical space. If you’re experiencing a feature in IMAX, you will be serenaded by the sounds of a shattering sound barrier.

“WELCOME TO XXX, WHERE THE MOVIES….”

“AT XXX, YOU ARE THE AMUSEMENT…”

“ONLY AT XXX WILL YOU EXPERIENCE COMPLETE ORGASMIC ELATION”

But in a repertory theater, a film hits different. The lights dim ever so slowly until the room is veiled in complete darkness. A extended silence, tense and pregnant with excitement, envelopes the room. It all lasts a hair too long and then, suddenly, you hear the flipping of a switch from somewhere far above you—another room.

Then, the moment of truth: A faint flickering noice. A steady hum. Film being fed through a projector. A central beam of light hits the main stage, projecting an image. Then, an accompanying soundscape.

The film has begun.

THE BRUTALIST tells the story of renowned architect, László Tóth. A survivor of the Holocaust, the Hungarian Tóth is forcibly separated from his family and has to start his life anew in America, where he is forced to assimilate into a culture that doesn’t respect him.

Running at three hours and thirty-five minutes (a tad longer than my drive to the theater,) THE BRUTALIST can be described as an epic, but one that operates like a chamber piece.

It is a film about labor and material; large buildings and hollow rooms, mined from the imaginations of creative architects. Spaces in which titans of industry talk shop and enterprise, unperturbed by the gargantuan feats little men reach to accommodate them.

On the one hand, it’s a story about the American dream, about immigration. On the other, an exploration of artistic talent and those who seek to exploit said talent.

Because of the unconventional arrangement of the Enzian (the dinning room experience; a hip and informed patronage; fifteen minute intermission) the experience of watching THE BRUTALIST was elevated. It felt like I was taking part of an important occasion. But of course I was. I drove over three hours to watch a film that ran over three hours, just to hit the road back home…for three hours.

A casual visit to the cinema was transformed into an event. Conversations sparked during intermission were potent, the air, rife with ideas. It was like watching an Opera at the Lincoln Center. Discount movie Tuesday, this was not.

In the past fifteen years, filmmakers have pushed for special screenings of their movies projected on film, in part to drum up attention to their latest projects. Directors like Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Christopher Nolan take their pictures on the road, across major cities, akin to a traveling roadshow. Movies that would have otherwise lived and died at the AMC were now eventized extravaganzas.

I surrendered to a unique experience that few can enjoy. Something old, from a bygone era. In an increasingly digital world, analog projection felt new. It felt punk. something for the underground crowd.

And yet…it wasn’t. In truth, these modern filmmakers are tapping into an old, time-weathered tradition which began at the turn of the twentieth century, when the notion of moving images was but a glint in the eye of a handful of inventors.

Viva la cinématographe!

Paris, France 1895.

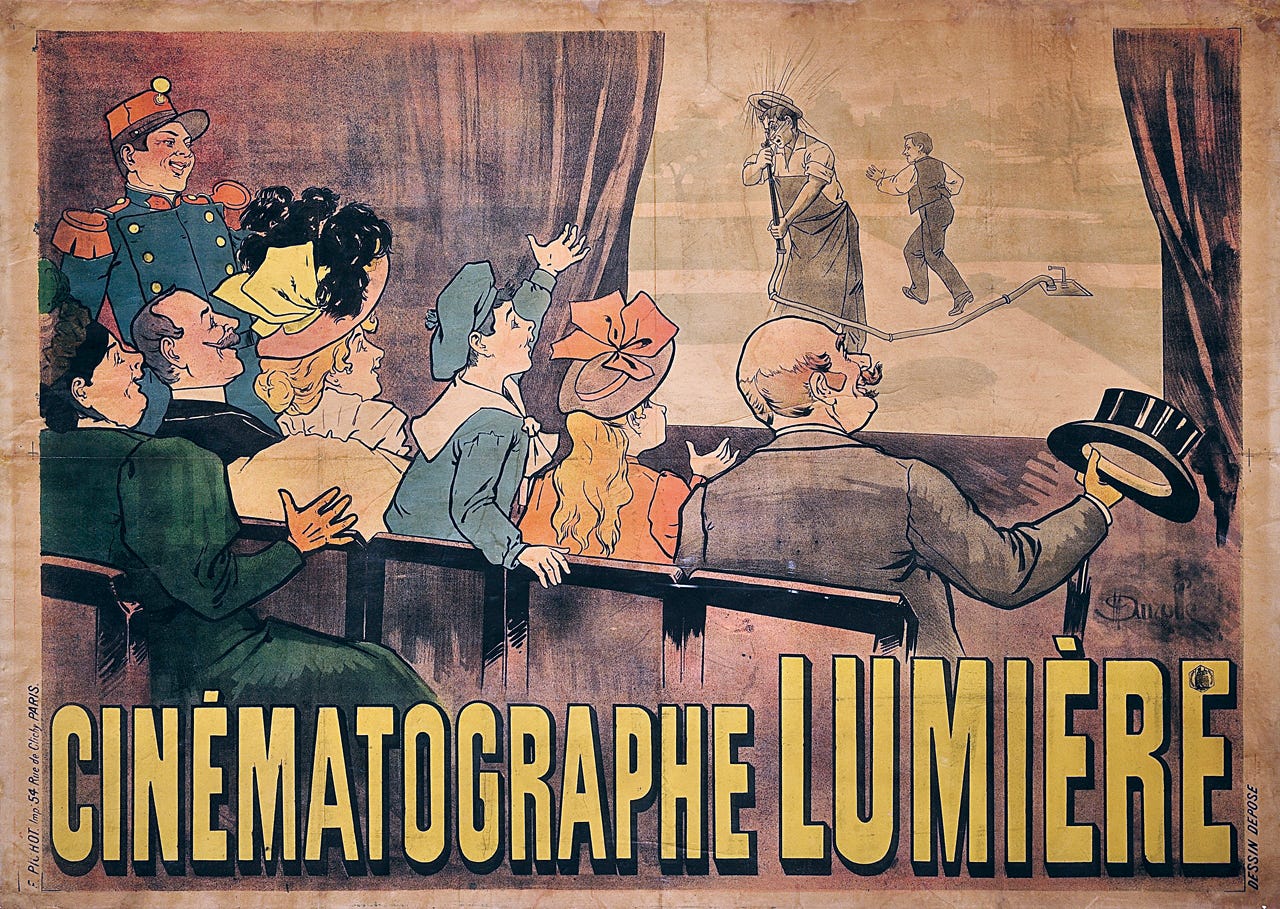

French inventors, Auguste and Louis Lumière gaze triumphantly at their latest invention, the Cinematograph. Acknowledged as one of the first motion picture cameras, the Cinematograph was unique in that it could capture moving images in using film. Once developed, the film could be project in any darkened spaced.

As forward-thinking pioneers of the new medium, the Lumière brothers brainstormed ways in which they could shift towards exhibition. They ultimately found inspiration in the oldest roots of show business. Namely, the traveling minstrel show.

This was a time before multiplexes, when screenings were set up in cafe basements, bars, and hotels. Posters were distributed across Paris serving as advertisement, touting the new entertainment of the 20th century. Come one, come all.

For the occasion, the Lumière brothers put together a series of ten short films, each averaging 30-45 seconds. These shorts— labeled Actualités—captured everyday life, untampered by the filmmakers.

The occurrences and themes varied: ticket holders at a horse race; women leaving a factory; gardeners in the field; a couple, feeding their baby.

One of the earliest screenings, taking place at the Grand Café on the Boulevard des Capucines in December of 1895, brought together over forty guests. By most accounts it was the first recorded instance of a commercial public screening.

People’s minds were blown. Tales spread of a new contraption which brought images to life. Later, the brothers would screen another short titled The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station, which featured a train slowly entering a station.

Legend has it that audiences were leaping out of their seats, believing that the locomotive would burst out of the screen. Talk about edge-of-your-seat entertainment. These screenings quickly proliferated, crossing the pacific, where American filmmakers raced to film their own projects, their own events.

General stores across the United States were repurposed into screening rooms where audiences paid a nickel to watch shorts (hence the birth of the Nickelodeon).

As the technology advanced, so did the possibilities of moving pictures, now labeled movies. The language of cinema matured. Narratives could now be expressed visually, and with the assistance of sound and color. An entire suite of jobs were manifested. Actors, cinematographers, gaffers, set designers, directors, writers.

It takes a village to bring epics like GONE WITH THE WIND to the big screen. CASABLANCA would not be what it was without the onscreen charms of Humphrey Bogart. CITIZEN KANE reminded us that the medium was young. It’s potential, vast.

Over the decades, film solidified itself as THE dominant art form of the 20th century. But, like any in commercial enterprise, change becomes necessary. How do you maintain support from audiences? Drum up excitement? Eventually, audiences get bored.

During the 1950’s, television experienced its own mini renaissance. Gunsmoke, The Honeymooners, I love Lucy, and Leave it To Beaver greeted audiences in their homes after a day at work. The prevailing question became: Why would I go to the movies when I can stay home and watch an adequate sitcom, T.V dinner in hand?

The studios were faltering. There was an air of panic, a feeling that movies needed to evolve in order to survive. If television offered weekly escapades into the lives of Marshal Matt Dillon, and Lucy Riccardo, films needed to pivot in the other direction. Into the realm of sheer spectacle.

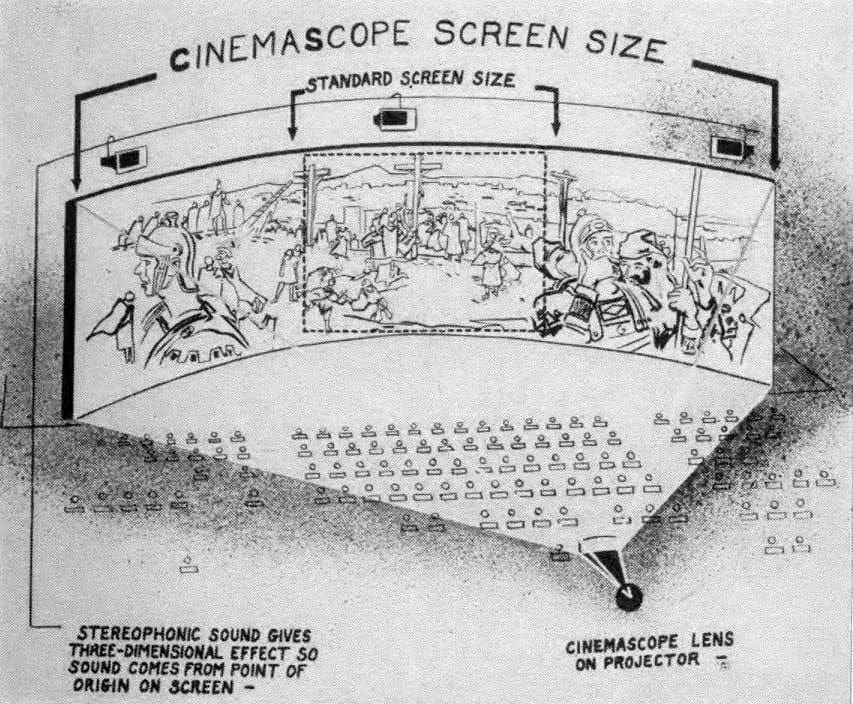

And so, the movie screens got bigger. Budgets ballooned to accommodate more star power, practical effects, varied locales, and marketing. Words like CINEMASCOPE, PANAVISION and TECHNICOLOR splashed onto the screen, accompanied by a blaring fanfare! Big formats meant to accommodate big productions.

The names of stars littered the billboards and magazines. Steve McQueen, Elizabeth Taylor, Natalie Wood, Paul Newman, Audrey Hepburn, Sidney Poitier, Elvis Presley. They were beautiful, glamorous.

These stars weren’t homely, like the kind that exist on television. They were unobtainable—beyond reach. Accessible only for the price of admission in a darkened theater.

Audiences were promised sharper images and a full breath of sound. Entering the mid-50’s, the narrative became: If you’re a fan of visual stories crafted by great directors, pay for a babysitter and book it to the movies.

This is how you beat the blight of television. If it worked then, maybe it can work now. In fact, it already has…

Sinners, all!

In early 2024, the word was that Ryan Coogler, director of the BLACK PANTHER movies, was gearing to direct his next original film. Details were vague. It was to be an original horror story, staring long-time collaborator, Michael B. Jordan.

Then we learned about it’s production. Namely, the project’s utilization of Panavision, and IMAX film to deliver the sharpest experience. Anticipation mounted after audiences learned that IMAX was the best way to experience Coogler’s latest.

And just like that, we had an original film, from a young, talented filmmaker, garnering support for a format that few can actually experience. A feat virtually unheard of in this moment of streaming television.

SINNERS tells the story of 1930’s Chicago gangsters, Smoke and Stack. The twin brothers return to their home town of Clarksdale, Mississippi to pursue their fortune. Their venture? A juke-joint. A respite for the local flavor offering strong drink and folk music.

As the brothers are confronted by the sins of their immediate past, more ancient evils announce themselves, potentially shattering their attempts to reform.

SINNERS released in theaters to massive praise from critics. More importantly, it was a word of mouth sensation. I’ve had people contact me, in person or through text, friends who have no business visiting the AMC, losing their minds over SINNERS. My parents have seen the film, and they barely speak english.

The marketing worked on me, that’s for sure! I set out to find an ideal screening in Florida, which led me to Fort Lauderdale. The Museum of Discovery & Science, offered the best viewing experience for SINNERS in full IMAX. Given it was day of release, I’d figure the crowd would resemble one that you might find at a film convention—nerds prancing around, guffawing about their recent escapades at cinema-con.

No. They were casual crowds. Majority black. All excited to see the newest Michael B. film where he clobbers vampires. My audience had fun. They laughed at all the right jokes, hollered at moments of drama.

Like all great art, SINNERS persisted on it’s amazing story. The tech utilized to bring Coogler’s vision to life was ancillary, for sure. The cherry on top. But! It is pertinent to note how far people would have gone to watch SINNER’S in a format that harkened back to an older era. A marketing strategy that has spelled success time and time again. With the advent of sound, then color, then 3D.

Imagine it—we are over one hundred years removed from that fateful Paris screening of Women leaving a factory, and we as audiences are STILL finding enticing reasons to file into a darkened room, to watch films projected onto a back wall.

The recent success of film screenings remind me of the success of vinyl in the last fifteen years. These are mediums in conversation with one another—both antiquated, and thought to have been erased from existence, only to come back with a vengeance.

Things seem to be in an up-tick. As they were in the 1920’s and the 1950’s and so on and so forth. If there’s one constant, it’s that nothing is new under the sun.

Thank you to Ryan Coogler for committing to the form, and the Enzian for giving these experiences a home.

Catch SINNERS in IMAX while you still can! Otherwise, catch it on MAX on July 4th.

Hey, I’ve started an account where I collect some out of context captions of great films in cinema history. Just wanted to share it with the cinephiles around here : https://substack.com/@pariscinema?r=1x6h4r&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=profile